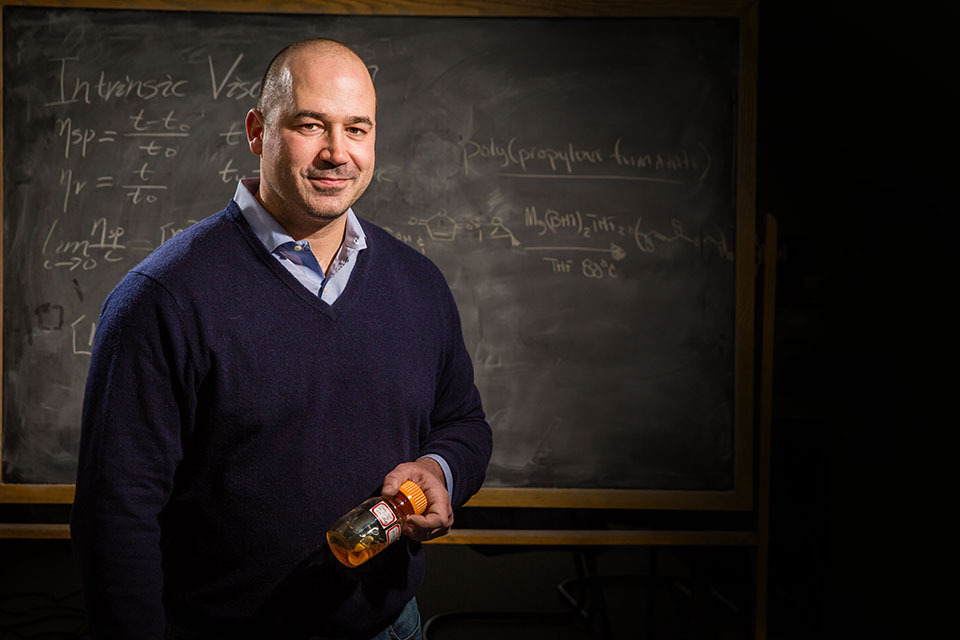

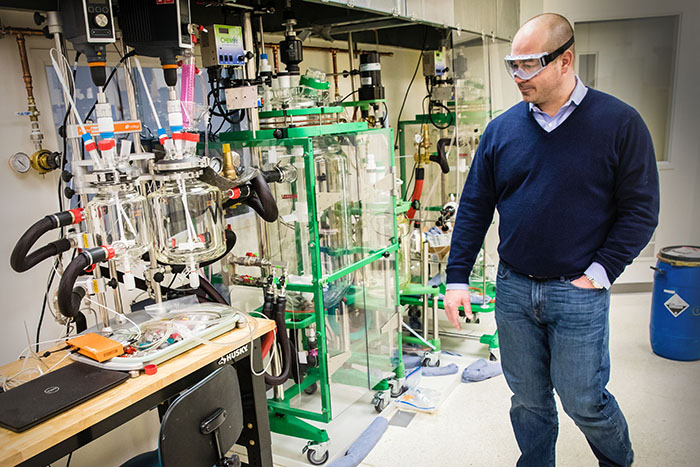

Matt Becker, a 1998 Northwest alumnus, is a polymer scientist at the University of Akron. Holding a bottle of fluid his research team developed to make polymers, Becker insists on using chalkboards in his office and classrooms because they force him to explain concepts to his students more slowly. (Photos by Todd Weddle/Northwest Missouri State University)

May 9, 2019

This story appears in the spring 2019 edition of the Northwest Alumni Magazine. To access more stories and view the magazine in its entirety online, click here.

With all of the honors and achievements on his résumé, Dr. Matt Becker ’98 remains unapologetically proud of his Northwest connection because his teaching philosophy and research are rooted in the experiences he had there.

Prominently displayed on the top shelf of a bookcase just inside the door of his University of Akron office are photo plaques of the Bearcat football teams on which he played during the late ’90s – an experience that instilled in him the ideals of hard work and perseverance he emphasizes with his students today.

Across the room, on a bulletin board behind Becker’s desk, a thumbtack holds a photo of the grave marker for Matt Mason ’98, who was killed in 2011 with his Navy SEAL team during a mission in Afghanistan. Becker and Mason, a Bearcat baseball player, were friends and lockered near each other in the Lamkin Activity Center. Becker’s wife, Lisa Sears Becker ’98, and Mason’s widow, Jessica Boynton Mason ’00, were sorority sisters. The photo is posted purposefully at the eye-level of Becker’s chair to remind him of the reasons for his life-changing work and “that every day is important.”

Becker, a polymer scientist at Akron, and his multidisciplinary research team are devising and creating medical advances that boggle the mind. Their work focuses on synthesizing macromolecular materials to stimulate and influence cell functions and, in turn, impact biomaterials, regenerative medicine and the detection of diseases such as cancer.

They are making artificial blood vessels and degradable elastomers for ligaments and skin. One project involves 3D printing technology to create plastic implants capable of sealing small holes in skulls. Another project involves the development of a degradable polymer film that could be loaded with a non-opiate pain reliever and implanted into a patient after surgery, thus reducing the need for pain pills after surgery and combating the nation’s opioid crisis.

Since arriving at the University of Akron a decade ago to join the faculty in its Department of Polymer Science, Becker, who serves as its W. Gerald Austen Endowed Chair of Polymer Science and Polymer Engineering, has launched three startup companies and has his name attached to 50 patents, either issued or pending, including more than 20 filed in just the last year. He’s raised more than $25 million for his research and leads one of the country’s biggest research groups in his field.

|

| Becker, a polymer scientist at the University of Akron, and his multidisciplinary research team are devising and creating medical advances, including the Mason Shell. |

Although it helped that Northwest had a strong science program, Becker enrolled at Northwest on a football scholarship in the fall of 1994. He began as an English major with thoughts of becoming a journalist. His freshman composition instructor, the late Leland May, thought otherwise. So Becker grew serious about finding a path in medicine or pharmaceutical work.

“He told me I wrote like a scientist and I should scratch that itch,” Becker recalled. “So I tested out of all English. I just had to take his honors comp class, which was really writing intensive. I had really good science teachers in high school, and I had a lot of interest in science.”

That same fall, Becker was a tight end on the Bearcat football team that took a beating and went 0-11 to begin the Mel Tjeerdsma era at Northwest. The season had been so difficult to endure that Becker wanted to quit. But some “tough love” from his father, combined with the bonds Becker had started forming with some of his teammates, convinced him to stick with the program. It paid off as the Bearcats were a winning program the next season and Becker’s leadership as a student-athlete helped the program become a national championship contender by the time he finished his career.

“The first couple years, it was hard to get the right team,” Becker says, noting the parallels of his football career with building his research groups at the University of Akron. “Then you get the right team and you have some success, and then it’s easier to get the next person.”

|

|

Becker models his teaching style and interactions after his mentors at Northwest. “You need something from everybody, and even though I’m pushing hard for what I want to accomplish and they’re on my team, what they want to accomplish is different than what I’m trying to accomplish,” he said. “It’s in line, but their goal is different. You’ve gotta respect that, too.” |

|

| Becker was a four-year member of the Bearcat football team -- an experience that he says helped toughen him for graduate school. |

|

After graduating from Northwest, Becker headed to Washington University in St. Louis to pursue a Ph.D.

He credits his football experience for much of his success, including the mental preparation and toughness to handle the rigors of graduate school. Becker was one of 32 students to begin the Washington University program and one of 16 to finish it.

“My skin was really thick at that point,” he said. “A lot of those people that didn’t make it, part of it wasn’t because they weren’t smart enough. They just weren’t mentally tough enough. Some of the people that failed out were from Michigan, Princeton – good places. The Northwest Missouri State guy made it.”

When Becker completed his doctoral work in 2003, he received offers to work with federal defense labs and start-up companies in California. He had post-doc offers at Harvard University and Imperial College London. Instead, he chose to pursue a post-doc opportunity at the National Institute of Standard Technology (NIST) in Washington, D.C. After two years there, the agency hired him as a staff scientist, and he participated in its research of pharmaceutical drug distribution through solids in polymers.

By the end of the decade, Becker, through his work with Walter Reed Army Medical Center to support injured veterans, had ideas for building a program in regenerative medicine. He also had established connections at the University of Akron, which is renowned for its polymer science and polymer engineering college. So when the dean of the college offered him a job, he took it.

“When I went to work for the national lab, that’s really a dream job for a lot of people, and I loved it,” Becker said. “I could not do the stuff I am doing now without having spent almost seven years there. I learned a ton — what I’m good at, what I’m not good at. I didn’t think I’d ever leave, and then things change. I really wanted to do something I couldn’t do there.”

Becker is one of 22 faculty members in Akron’s polymer science department, which is one of just four polymer programs in the country. He teaches graduate and undergraduate courses to about 60 students a year. His research team averages about 25 members and has graduate students from eight countries. A fair number of them will end up at Ph.D. programs spanning the globe and then at major companies such as Intel, 3M, NIST, Exon-Mobil, Pfizer and Cook Medical.

“I have good students, good colleagues,” Becker said. “I don’t treat it much different than Mel built his football team. Hire the best people you can hire, coach ’em up, lots of tough love even when they don’t want it, and try to get the most out of every person you can, recognizing they’re all different and play to their strengths. Some make it, and some don’t.”

Much like the process Tjeerdsma and Co. endured when they were rebuilding the Bearcat football program, Becker had to figure out how to recruit the right people to his research teams and raise the funding he needed to achieve the medical advancements he envisioned.

“I found that even like playing college football and graduate school, you need something from everybody, and even though I’m pushing hard for what I want to accomplish and they’re on my team, what they want to accomplish is different than what I’m trying to accomplish,” Becker said. “It’s in line, but their end goal is different. I am building a body of knowledge; they are building a future. You’ve gotta respect that, too. Just constantly be aware and recognize the problems before they start fires.”

He adds, “If I’m doing my job, companies are tripping over themselves to hire my people.”

Another Northwest memory not lost on Becker is the hospitality coaches’ families and community members showed him and other Northwest student-athletes – something else he models for his students now. He invites them into his home a few times a year, including a Thanksgiving feast for 54 last year.

“When I have potluck at my house, some pretty incredible stuff shows up,” he said. “My kids love it. I think it’s great exposure.” Becker says the mentors he had at Northwest made an overwhelming difference in the trajectory of his career. “Having really good mentors makes the difference,” he said. “I had ’em on the football team, had them in the classroom, had them in the community.”

And because of the adversity he learned to overcome – whether it was suffering through defeats on the football team or struggling through graduate school – he isn’t afraid to let his students struggle a little with their research challenges.

“If a student comes in here and I know exactly what’s wrong, I often don’t tell them,” he said. “I want them to suffer a little bit. Think. Struggle. Work through it. That’s part of the education process. If they can’t get over a hump, then I’ll push them over the hill a little bit. By then, they figure out that I know how to solve it and I’m not going to tell them. Then they go back and think and know that it’s solvable. It’s just part of the process of teaching them how to work through things that they haven’t done before.”

|

|

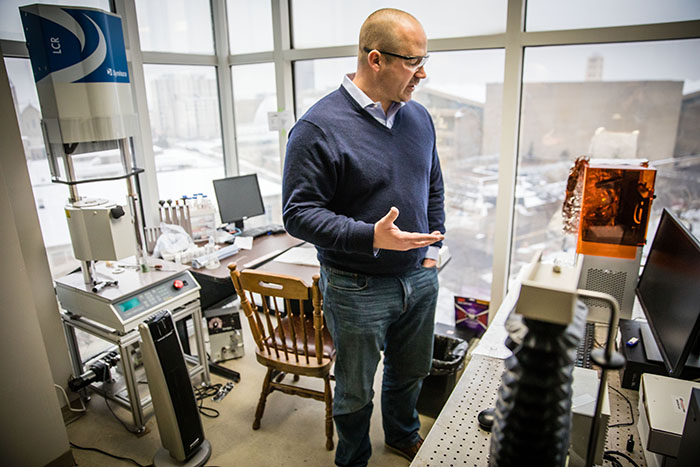

While most research groups only participate in pieces of a product’s development, Becker, pictured in his 21MedTech lab, and his group take it all the way from chemistry to widget. In 2015, his research team at the University of Akron received a $6 million grant from the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materials Command for the Mason Shell. |

|

| Matt Mason |

A few years ago, when Becker’s research group needed industry partners to test the materials they were creating, he launched a start-up company. That idea grew and evolved into 21MedTech, an umbrella company for three start-ups Becker founded to focus on materials and drug distribution for medicine.

They create building blocks to make polymers, which are plastics that degrade in the body and have applications for bone, marrow and muscles. Its largest project focuses on degradable polymers for military medicine, and that’s where Becker’s connection with his friend Matt Mason comes in.

The “Mason Shell,” as it’s tentatively named, is a cylinder-shaped shell Becker’s team created to save the limbs of soldiers injured by improvised explosive devices or gunshot wounds. The shell is made of amino acid polymers and inserted into a gap in the bone using a methyl methacrylate glue commonly associated with dentures. Within a couple of years, the shell degrades while the bone regenerates and heals.

Becker’s science writing has paid off in the form of millions of dollars in grant awards. 21MedTech is making the material, and the shell has been successful in sheep, which possess many of the same bone characteristics as humans. Becker is hopeful the Mason Shell will be in a soldier within a year.

“If you really want to push things like the Mason Shell – things you care about – you’ve gotta suck it up and not be afraid to fail,” says Becker, who received the Northwest Alumni Association’s Distinguished Alumni Award last fall.

Becker’s story is far from finished, however. This summer, having developed his research beyond the capabilities of Akron, he’ll take his research group to Duke University, which recruited him this spring to join its departments of Chemistry, Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science, and Orthopedic Surgery.

“I’ll actually be embedded in a surgery department, so I’ll be in chemistry, surgery and engineering,” he said. “While I’ve been successful at Akron, many challenges remain. We’ve been able to do the things we wanted to do so far, but we want to take the next step and put these materials in humans. That requires a new team.”